In and Out

pt3. Shifting Perspective

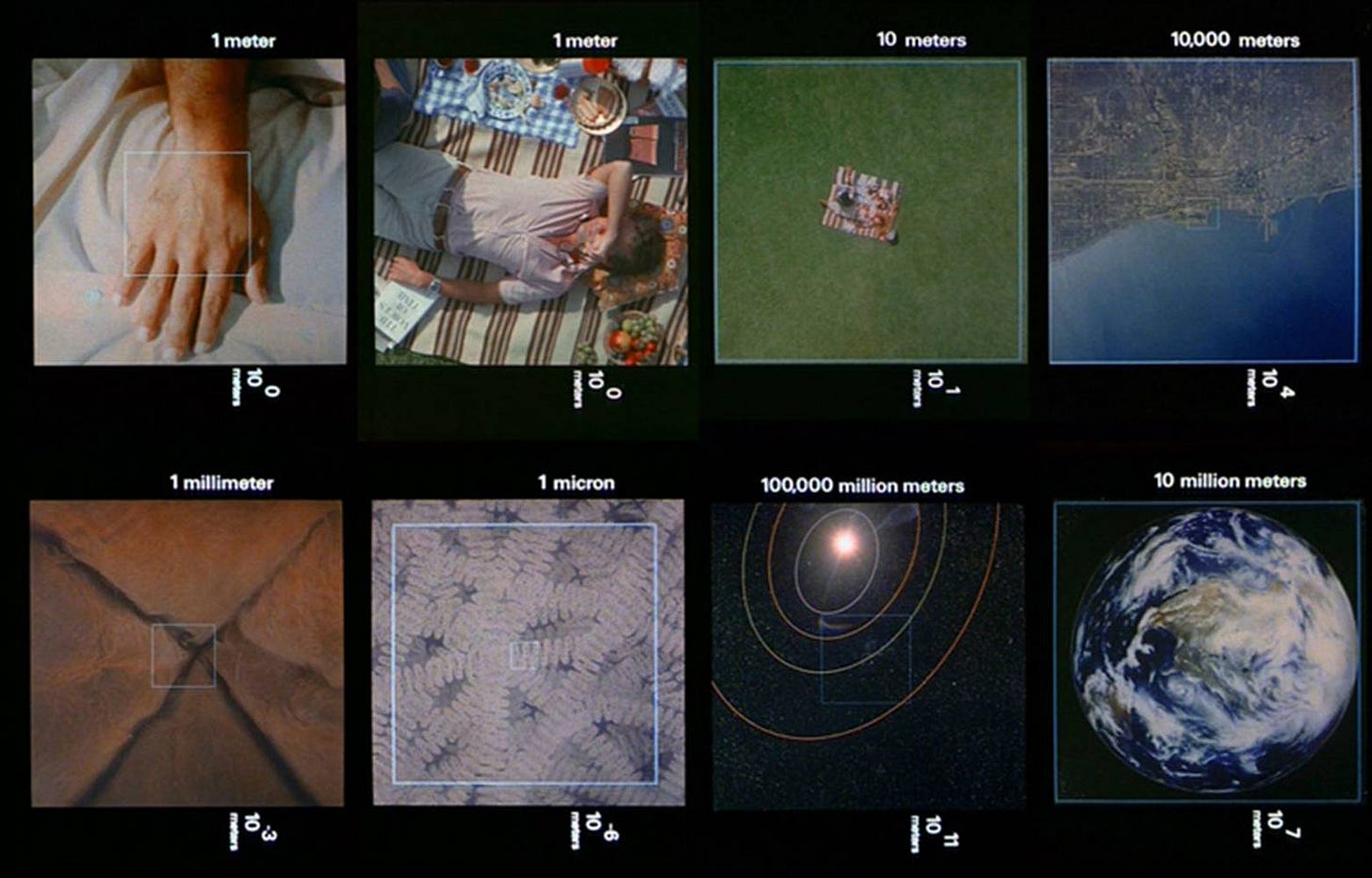

Our relationship to an idea is shaped by proximity. Up close, we encounter detail; texture, irregularity, and the visible traces of process. From a distance, we perceive composition; how elements connect, and how the whole comes into coherence. Each viewpoint offers a different aspect of truth. The real value comes in toggling between the two, like adjusting a camera’s focal length or walking around a sculpture suspended in space. It’s a form of visual thinking, a way of checking your own narrative.

The movement between macro and micro (abstract and specific) is anchored in presence. Presence isn’t stillness; it’s engagement of awareness. It’s knowing where you are and when to pull back or when to lean in. The clarity of your intention is what allows perspective to shift in meaningful ways. Noticing is the entry point to awareness.

Time alters our relationship to problems, to moments, to meaning. A pressure point today can dissolve into clarity tomorrow. Something mundane can accrue weight with distance. Time (an abstraction) offers the ultimate vantage. "How will this look next year? What am I too close to?" This temporal shift in altitude gives perspective more than just shape as it gives depth.

Often one thing is a chain of events. Zooming in leads to a hyperfocus on detail; precise specifics, stylization, nuance... but zoom out, and you begin to notice systems of interconnection; relationships, proportion, context, theme, metaphor, patterns, etc. The same truth reshapes itself at every scale. At one level, all is one. At another, everything fragments. The mistake we make is assuming only one view is correct. Both are true, at the same time.

One of the most practical tools for shifting perspective is reframing (reorientation). Asking new questions opens new views: “What am I not seeing?”, “What really matters here?”, “What if this problem belonged to someone else?”, or even “What if this wasn’t a problem at all?” Framing is how we define problems and sometimes it's where we get stuck. Reframing changes the structure of thought and separates signal from noise. It interrupts default patterns, loosens fixed assumptions, and opens space for alternate meanings to emerge.

Psychological distance expands this further. According to Construal Level Theory, the more removed we are; spatially, emotionally, or temporally the more abstract our thinking becomes. That abstraction can free us from constraints as often one thing can have many meanings inside it. A vegetable transforms into material, energy, metaphor, a verb, etc. It’s a shift in recognition as (re)seeing the familiar creates space for new meaning.

Another shift can happen by stepping into different roles or by using mental tools like ‘thinking hats.’ What would the skeptic say? The optimist? The outsider? The user? The 10-year-older version of you? Tools like this are lenses to the camera. Each one changes what is being seen as they force elasticity and that elasticity (the capacity to expand and contract your view) is a kind of creative fluency.

Ultimately, perspective-shifting is knowing when to move. Timing matters. Precision matters. Too much zoom, and you lose the whole or too much distance, and you miss the nuance. The aim is to consciously calibrate and if you do it enough, it becomes natural.

Perspective isn’t a trick. It’s a discipline, a muscle, a form of care. In creative work and daily life, it’s what lets you hold complexity without disappearing into it. The goal isn’t to always shift, but to shift until the blur sharpens, the noise settles, and the form slowly comes into focus.

Links: Cina Associates, Cina Art, Public Type

‘The same truth reshapes itself at every scale…. The mistake we make is assuming only one view is correct. Both are true, at the same time.’

A post dense with concepts as always Michael. Thanks for the creative nourishment. Will take me the week to digest it all.

Another post I know I’ll be coming back to many times. Thanks for sharing this!