As we move through life, we often overlook details like the cracks in the pavement, the scuff marks on the wall, or the work we’ve been immersed in for months. These elements fade into the background, becoming part of the familiar daily landscape we pass by. As we age, curiosity about the familiar often fades. This causes us to take our surroundings and routines for granted, missing the awe and wonder that once captivated us.

Noticing calls for awareness, an engagement, curiosity, and self-reflection. The problem doesn’t lie in what we perceive, but in how we perceive it. By creating space for observation, we uncover the potential for discovery. When we observe without distraction, the ordinary reveals its hidden stories, leading to deeper insights and possibly unexpected breakthroughs.

We all carry a preconceived worldview; a set of assumptions, biases, and beliefs that shape how we interact with the world. While this lens helps us navigate life efficiently, it also blinds us to what’s right in front of us, particularly when things don’t fit into our predefined categories. The challenge is not to interpret events in a way that reinforces our worldview but to accept them as they are, without trying to fit them into our biases. By letting go of these mental filters we can re-see, approaching the world with a fresh perspective.

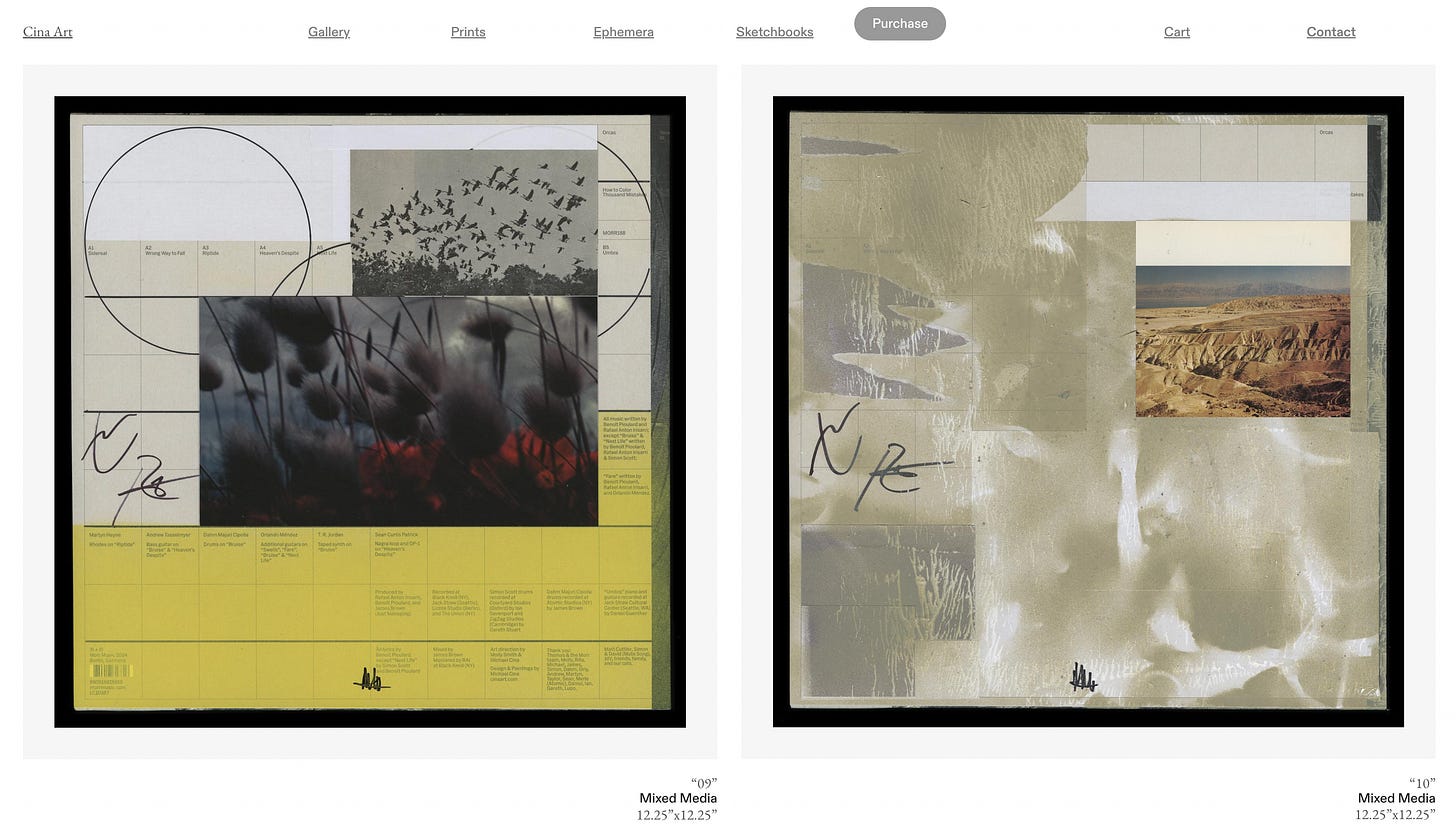

In design, the mundane often holds the most direct and powerful ideas. Objects we overlook can offer solutions when viewed with fresh eyes. Just as Newton’s apple led to the understanding of gravity, everyday objects can spark new thinking. Much of design is about finding connections between the mundane and the sublime. I enjoy photographing cracked signs, finding strange juxtapositions, and appreciating the ordinary just as I do works in galleries. It's about seeing what others miss because we allow ourselves to notice the details.

In a world that demands speed, I often forget the priceless value of being present. It's only when I slow down and give space (time) to the moment that the mundane becomes extraordinary. Even the most mindless tasks, when approached with intention, can take on deeper meaning. This shift in perspective mirrors the practice of looking at the world with a "beginner’s mind" free from assumptions and preconceptions. It's not about naivety or tricks but peeling away the layers of habitual thinking to see things anew.

The mundane is frequently overlooked in favor of more urgent tasks, but it often holds a quiet tension. Every object, every experience, is an opportunity for transformation. The cracks and imperfections we encounter aren’t mistakes, but evidence of time, use, and life. These imperfections create deeper, more authentic stories, reflecting a larger narrative about our existence.

We can use a camera lens filter as an example. It’s designed to alter an image, often to enhance a photograph or produce specific features (distortion and clarity). It is also made to solve practical problems, like protecting the lens and reducing reflections and glare. Our worldview also acts as a filter, shaping how we see objects and situations based on assumptions and values. Design researcher Dori Tunstall notes that objects, like camera filters, are influenced by cultural values. They symbolize not just technological progress but also our desire for beauty, clarity, and understanding. Just like a photograph can become more true to life when we remove a distortion filter, we only see these objects fully when we let go of the mental filters we've assigned to them and see the fullness of their purpose.

The paradox is that to notice more, we must become less focused. By detaching from the urgency of the world, we begin to absorb its subtleties. The mundane is never truly mundane as it’s waiting for us to notice it, to question its existence. In doing so, we can uncover its hidden depths, engage more deeply with the world, and create meaning rooted in the ordinary, yet pointing toward the extraordinary.

What makes things matter to us? "What exists" is not the same as "what matters." The mere presence of things around us does not guarantee significance. Something matters only if we care about it or pay attention to it. This concept resonates with phenomenology, the study of experience. As William James said, “My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind.” Without our attention, things remain obscure and meaningless. This is central to how we construct our reality.

Similarly, Heidegger’s concept of “being-in-the-world” suggests that meaning isn’t something we impose on the world because it’s inherent in our very existence. This emphasizes that meaning (thus worldview) arises through our engagement with the world. We are not detached observers; we are immersed in a world of meaning that we continuously shape through care and attention. Objects matter when they capture our attention and are invested with significance in our minds. Meaning lies not in the objects themselves, but in how we engage with them and what we choose to give our attention to.

Links: Cina Associates, Cina Art, Public Type